The Impact of COVID-19 on Women in Law

Dubravka Tosic

Female attorneys—especially Black female attorneys—left the workforce in droves during the pandemic. The industry needs to act.

During COVID-19, over 104,000 female attorneys dropped out of the labor force. Almost 37% of those were Black. The number of Black female attorneys active in the labor force dropped by 55% during the pandemic. Here’s why it may have happened—and what the industry needs to know and do now.

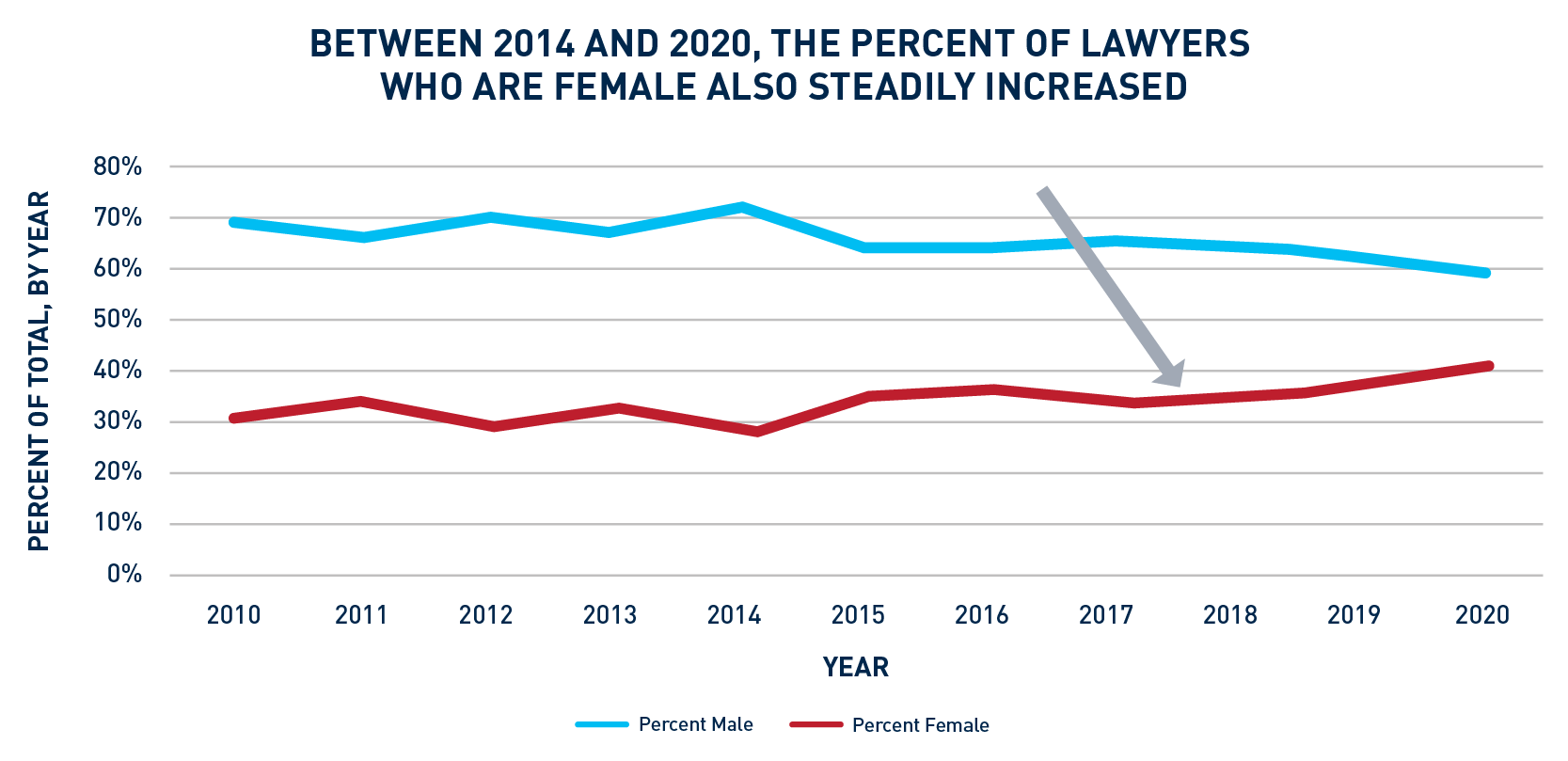

In the past decade, and especially since 2014, steady progress has been made in terms of the number of female attorneys active in the U.S. labor force.[1] While the overall number of active attorneys in the United States increased from 1.22 million in 2014 to 1.24 million in 2020, the number of female attorneys increased by almost 46%, from around 347,000 in 2014 to about 506,000 in 2020, according to U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Survey (CPS) data.[2]

Similarly, while 28% of lawyers (at all levels) in 2014 were female, about 41% of lawyers in 2020 were female, a 13% jump in the seven-year period.

This increase is a testament to efforts made by many individuals and organizations at each point of the talent pipeline—from law school admissions and successful graduations to law firms and advocacy groups.

Women in U.S. Law Firms

The National Association for Law Placement’s (NALP) 2020 Report on Diversity in U.S. Law Firms finds similar patterns. Based on survey results, the NALP reported that in 2020, 37.1% of all lawyers were women and 9.32% were women of color.

The well-known and unfortunate statistic is that the percentage of lawyers who are women varies widely by level: about 50% of law students and summer associates are women, but as they progress through the ranks of law firms, their percentages decrease drastically. In 2020, 25% of partners and 21% of equity partners were women. For women of color, the percentages are lower: 22% of summer associates and 4% of partners. Similar patterns can be found in corporate America in general. According to McKinsey & Company's Women in the Workplace 2021, while women held 48% of entry-level positions in 2021, they held only 24% of C-suite positions. Women of color held 17% of entry-level positions but only 4% of C-suite positions. Women (regardless of race) fall farther behind in representation at each step of the pipeline. Female workers of color have stated that they often represent the “Double Only”: the “Only female” and the “Only person of color.”

The NALP study also shows that, except for “Non-Traditional Track/Staff Attorneys,” the larger the law firm in terms of number of attorneys, the higher the percentage of women and women of color. This statistic, on average, speaks to the organized efforts in many large law firms to attract, retain and promote female attorneys.

Many in the law profession have dedicated significant time and effort to identify the potential reasons an inverse relationship exists between years of experience and rank and the number of female attorneys (i.e., the higher a woman’s rank in a law firm, the fewer women are found with the same rank).

Roberta D. Liebenberg and Stephanie A. Scharf's pioneering study Walking Out the Door: The Facts, Figures, and Future of Experienced Women Lawyers in Private Practice, published by the American Bar Association (ABA), examines and identifies potential reasons why experienced women lawyers leave the legal profession, especially when they are in the prime of their careers.

The study ranks the top reasons experienced female attorneys cite as an “important” influence on women leaving their firm:

Caretaking Commitments

Level of Stress at Work

Emphasis on Marketing or Originating Business

Number of Billable Hours

No Longer Wishes to Practice Law

Work/Life Balance

Personal or Family Health Concerns

The study also finds that 50% of female partners were satisfied with the recognition they received for their work, compared to 71% of male partners. In fact, 14% of female partners reported that they were “extremely dissatisfied” with the recognition they received for their work, compared to 2% of male partners. These are large differences that should be studied and analyzed further.

Effects of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the trend of women lawyers leaving the labor force. The number of female attorneys in the labor force dropped from 517,000 in March 2020 to about 413,000 in August 2021. Within an 18-month period, there were about 104,000 fewer female attorneys in the labor force, representing a 20% decrease. As of October 2021,[3] the number of female attorneys had increased back to about 450,000, which may be a positive sign that women are reentering the workforce.

The below chart shows that the large decrease in the number of female attorneys has been due mostly to the reduction in the number of female attorneys of color, especially Black female attorneys.

The number of white female attorneys dropped from about 402,000 in March 2020 to 348,000 in August 2021 (a decrease of about 13% or about 54,000 attorneys), while the number of female attorneys of color decreased from about 116,000 in March 2020 to about 65,000 in August 2021, a reduction of about 51,000 attorneys[4] or almost 44%.

Specifically, the number of Black female attorneys active in the labor force dropped from about 71,000 in March 2020 to about 32,000 in August 2021. This represents a reduction of almost 39,000 Black female attorneys, or a 55% decrease.

Moreover, female attorneys of color, especially Black female attorneys, have been disproportionally leaving the workforce during the pandemic:

While pre-pandemic 22% of all female attorneys were women of color,[5] their representation dropped to 16% as of August 2021. In fact, 48% of the reduction in the number of female attorneys during the pandemic was due to women of color attorneys leaving the workforce (i.e., 50,000 of the 104,000 fewer female attorneys are women of color).

Similarly, while pre-pandemic 14% of all female attorneys in the labor force were Black, their representation dropped to 8% as of August 2021. This is because 37% of the reduction in the number of female attorneys during the pandemic was due to the Black female attorneys leaving the workforce (i.e., 39,000 of the 104,000 fewer female attorneys in the labor force are Black female attorneys).

While many studies to date have confirmed that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a harsh impact on women—with some calling it the “She-cession”—of interest for future studies is determining why the pandemic appears to have affected women of color, particularly Black women, most harshly. The latest figures for September and October 2021 show a slight reversal in the trend, which may indicate female attorneys starting to reenter the workforce (which coincides with the start of the school year).

The pandemic has intensified and highlighted many issues that female lawyers still in the labor force and working, and especially women with young children, face. About 80% of daycare centers either closed or became short-staffed during the pandemic. Based on monthly CPS data, between January 2020 and September 2021, almost 270,000 childcare workers dropped out of the labor force, and the number of unemployed childcare workers increased from about 62,000 in January 2020 to over 291,000 in May 2020.[6] Most schools moved to a remote setting, leaving parents to manage their children’s daily schoolwork.

The U.S. Census Bureau’s recently released Household Pulse Survey (Week 39)[7] shows that about 7 million of the 32.8 million individuals (or 21%) with at least one child four years old or younger did not have their child(ren) attend daycare due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Over 61% of the 7 million were women, and 44% were parents of color. In order to care for children, the overwhelming majority of these parents:

Took unpaid leave,

Used vacation or sick days, or other paid leave,

Cut work hours,

Left a job, or

Lost a job because of time away.

The domino effect is emerging: for many families, the lack of access to childcare resulted in children staying home, further affecting the work status of a high number of female workers. Only now are we starting to comprehend the significant and potentially long-term effects the pandemic has had on families, and in particular on working mothers as the prime caregivers of children and other family members (especially elderly parents).

The ABA recently published Practicing Law in the Pandemic and Moving Forward, a report by Scharf and Liebenberg. Their survey, conducted in September and October 2020 with over 4,200 respondents, found that:

Women were significantly more likely than men to have personal responsibility for childcare both before and during the pandemic. Additionally, women were significantly more likely to have taken on more childcare responsibility during the pandemic.

Women on average work a greater proportion of their hours from home than men. And, during the pandemic, attorneys did not see a reduction in the number of hours worked.

Over 90% of lawyers spend more time on video or conference calls, but about 55% spend less time on developing business or reaching out to clients. The presence of younger children in the household predicts even less outreach to clients.

Female attorneys, especially those with younger children, were more likely to report increased frequency of work disrupted by family and household obligations; felt it was hard to keep work and home separate; felt overwhelmed with all the things they have to do; experienced stress about work; and had trouble taking time off from work.

Women generally worried more often about advancement, receiving a salary reduction, and getting furloughed or laid off. Women with children felt more often than others that they were overlooked for assignments or client opportunities.

More women were thinking significantly more often this year than last year about working part-time, especially women with children ages 5 or younger and children ages 6 to 13 years old.

A Thomson Reuters Institute survey of over 400 attorneys conducted in February 2021 found similar results:

The two biggest barriers to career progression for lawyers during the pandemic were a) limited to no in-person contact and b) heavy workloads coupled with not enough time to complete work.

Female attorneys were disproportionately impacted by caregiving responsibilities and a lack of mentoring.

Lawyers of color reported challenges of flat structures; a lack of introduction to key clients, books of business and business development; and perceptions of racism, prejudice and bias.

Moving Forward

To break this pattern will require law firms, corporations, organizations, advocacy groups and lawyers themselves to recognize the impact of the pandemic on female lawyers and understand the reasons for these statistics. With this knowledge, action plans then can be prepared to reverse the trend. The studies cited above provide recommendations for action, as well as a call to measure progress through data collection and analyses. Many are starting to recognize that reversing the trend, making a meaningful impact on the return of female attorneys to the labor force, and retaining and promoting women lawyers will need to involve serious discussions and action on a number of topics, including:

Allowing flexible and/or hybrid work schedule arrangements

Encouraging employees to take care of their mental and physical health and to use paid time off and breaks during the workday

Changing policies that would impact parental leave, childcare and care for family members

Updating criteria used to measure and evaluate performance

Holding leadership accountable for defined goals for attracting and retaining female lawyers, as well as for diversity and inclusion

Actions to avoid creating siloed teams with little cross-firm interactions that could lead to stifled opportunities for business development, professional development and innovation

Inclusion of women, especially women of color, on various types of teams (e.g., pitch teams, client meetings, at trial)

Active mentoring and sponsorship, even during times of remote work

Longer-term, general cultural shifts where partner involvement in household care and services is fully accepted and normalized

I would like to thank Noel Williams of BRG’s Tallahassee, Florida, office for excellent programming assistance.

[1] Active in the labor force refers to workers who are either employed or unemployed but actively looking for a job.

[2] The data is from the Current Population Survey (“CPS” data), a monthly survey sponsored jointly by the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the primary source of labor force statistics for the population of the United States. The data presented includes lawyers only (Occupation Code 2100) and excludes other legal professions, such as judicial law clerks, paralegals and legal assistants, title examiners, abstractors, searchers and legal support workers.

[3] As of November 2021, the latest available monthly CPS data is for October 2021.

[4] Using definitions of race in the CPS data, women of color are defined as those women who do not identify as white. This means that the women of color definition also includes women who identify with two or more races.

[5] As of March 2020.

[6] As of September 2021, there were about 111,000 unemployed childcare workers.

[7] The survey was conducted from September 29 through October 11, 2021.